Since Heather was proactively planning Campus Equity Week this time, she reserved tables on campus during activity hours and lunchtime for three separate days, putting up flyers in the neighborhood in hopes of engaging the community. She also booked a computer and a flat-screen TV from media services to showcase a new playlist from her YouTube channel, Adjunct Life.

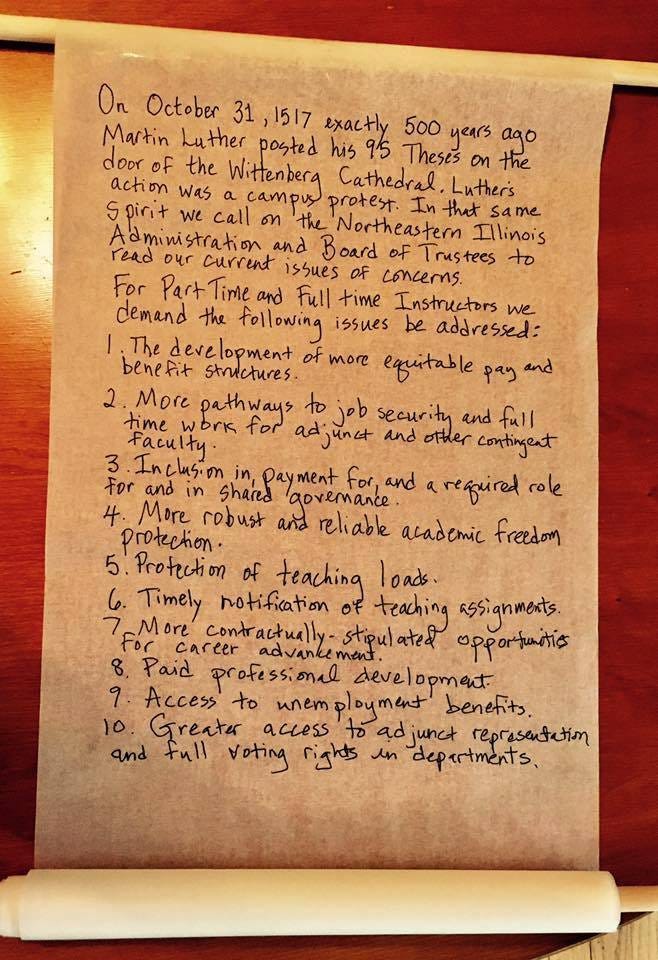

After extensive discussions with other instructors in the union, they decided to rewrite Luther’s 95 Theses to reflect the current crisis in higher education. Her plan was to parade to the administrative offices dressed in masks and academic regalia, posting their scroll on the door of the Administration Offices. This coincided with the 500th anniversary of the event, which falls on Halloween. The idea was to reenact the historical moment when Luther posted his theses as a campus protest against the Catholic Church.

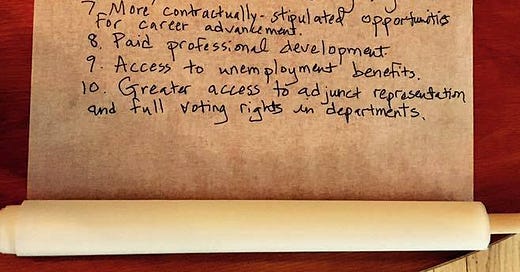

She purchased special archival paper and pens. Her idea was for students, faculty, and staff to identify what issues they wanted the administration to address. It began with a resolution that Heather had written as a delegate, which successfully passed at the 2017 IFT Higher Education Conference in Springfield, Illinois. Manuel encouraged her to run as an at-large delegate and nominated her in a meeting on campus. She won the position in the local election and had to write a statement in advance, highlighting her interest in supporting part-time faculty. She enjoyed attending larger union meetings in downtown Chicago and Springfield, where she met graduate students working on new contracts and part-time faculty from other state universities in her local area. She stayed in the hotel room provided for her, which she posted on Facebook with the slogan, “Adjunct Headquarters.”

She attended all the union meetings leading up to it and pleaded for help from other members. They looked at her with confusion and dismissal. The interim president of the chapter supported Campus Equity Week. He sent out email requests asking others to assist in the effort. Heather received few, if any, responses.

Heather decided to move forward and continued to try to drum up support in the meetings by making short announcements. “Well, listen, we are all swamped, and it’s very straightforward. All you need to do is show up, sit at the table, talk to the campus community about instructors and our issues here on campus, and let them know about the action on Halloween when we will post the scroll on the administrative office door.”

The other instructors didn’t warm to it at all. Partly, they disliked the Catholic overtones. Martin Luther had been rebelling against the Catholic Church, not the administration, several faculty members pointed out to her. They were uncomfortable with the idea that members should come up with their ideas about what was wrong with the university’s current administration. “People will sign anything if it’s well written, but who will take the time to put their thoughts together? It should be a petition.”

Heather wanted to know what students found important, as well as what the staff and faculty considered essential. She aimed to provide an opportunity to express what they believed was significant without any prior guidance on what to say.

Heather persevered, primarily because she had invested a significant amount of time talking to Andy Davis every Friday morning for over a year. She also engaged in email correspondence with her fellow adjunct activists, who were busy organizing various events on campuses across the country to bring attention to adjunct issues.

She stood up at the meetings and described the actions planned at other universities, but it had no effect. They looked at her with stony eyes. One day, her husband came home and said he had a new nickname for her: “You are a Gadfly. Listen, who cares if you don’t have support? Who cares if it doesn’t feel like a group effort? The main thing is to do it and get it done.” She loved how he supported her with her crazy ideas, especially this one.

The forum went well despite the other instructors' lack of enthusiasm. Many students attended, and surprisingly, several tenured faculty members also showed up, with the largest group consisting of chairs from their respective departments. These chairs had recently received emails informing them they would all be let go at the end of the spring semester. If the school became more financially sound, some might be rehired. The administration wanted to develop super-chairs who would oversee multiple departments simultaneously. The strategy was to save a significant amount of money and help alleviate the budget shortfall.

Heather had been contacted by several chairs who sought an opportunity to speak at the event or moderate the panel. She declined their invitations because, once again, she wanted it to be an adjunct forum. She didn’t want tenured professors hijacking the Teach-In. She was surprised they came regardless.

She was critical of academia and its protocols because they had provided her with so little support as a professional music educator. To Heather, these protocols reinforced a two-tiered system. That day featured a lively discussion with about forty attendees, but Heather believed the significance of their discussion mattered deeply. For example, if it had been recorded, adjuncts everywhere would have listened to it, as the issues were important not just on their campus but resonated across every university, college, and community college.

The tabling also went well that week. Several new adjuncts stopped by to ask questions. Staff members shared their concerns about the university’s future. Three hundred eighty civil service positions had been cut over the summer due to the statewide budget impasse. Heather and other union members spoke with them about the mismanagement of funds on large building projects and the hiring of highly paid administrators and public relations positions, contributing to that shortfall. The remaining staff were overworked and disillusioned. She felt their solidarity when several expressed interest in supporting part-time faculty.

Finally, the day of the great action arrived. Heather had finally succeeded in getting people to add their grievances to the scroll, and it looked impressive after all.

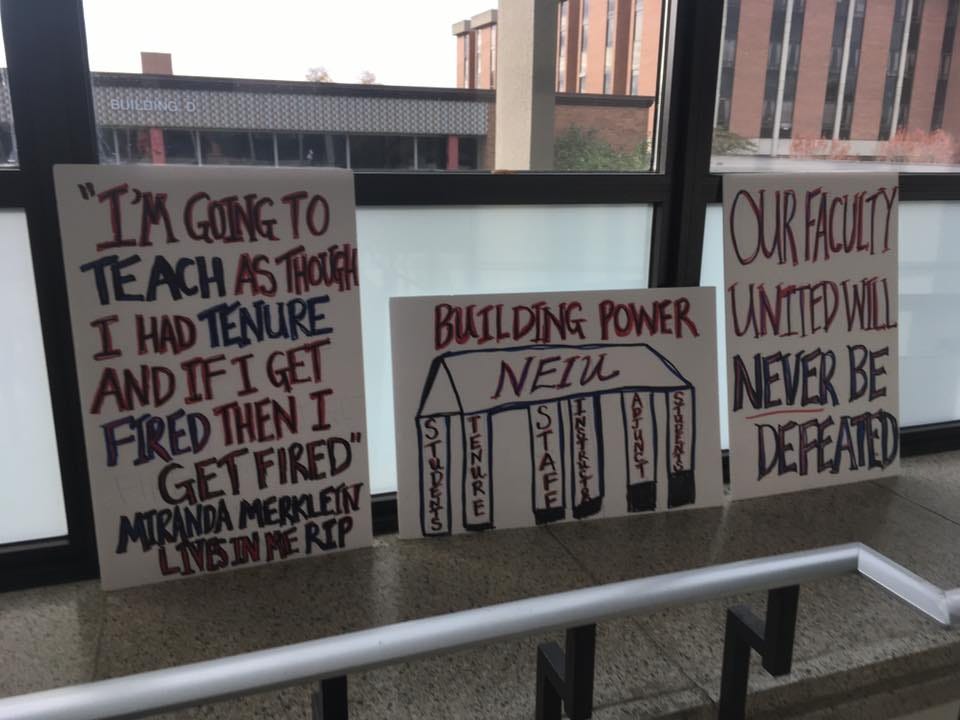

Heather purchased simple Halloween masks and brought markers and poster boards to the impressive room the union had reserved. She threw them on the large tables set aside for discussion between student groups and university advisory boards and collapsed in a chair.

Granted, it was Halloween. Granted, a well-attended Halloween party was happening downstairs in the cafeteria that offered cash prizes. Granted, there was a recital even she would have liked to attend, which conflicted with her department colleagues’ participation. Granted, she had bullheadedly continued organizing this event despite the apathetic and dismissive response she’d received from fellow instructors. She waited for one other person to arrive and realized sadly that nobody else was coming to join her.

She thought to herself, “Okay, I give up. The universe is trying to tell me something. The universe is telling me that this was a stupid idea. There is no reason you wasted twelve months trying to bring attention to these issues. Gather up all this stuff and throw it away, including the scroll. It’s enough already. Go home and wait for the trick-or-treaters like a good suburban mom.”

But then she thought about her friend Miranda Merklein, who had recently died alone in Massachusetts. Miranda was a brave labor organizer, an English professor, a writer, a mother, a grandmother, and a former adjunct. She lost her job organizing for SEIU and, consequently, her health insurance. At just 39 years old, she suffered from kidney failure and was afraid to go to the doctor because of the potential costs of hospitalization. They had been friends for four years, and Miranda had supported every action Heather organized and every piece she wrote about adjunct issues. They communicated on social media almost daily, keeping each other going in their common struggle for adjunct justice. How could she give up now? She remembered her mom’s words on the phone, “Fare Forward!”.

Instead, she texted her husband: “Jerry, I’m all set for this action, and nobody else showed up. What should I do?”

He texted back, “Grab the bullhorn and get ready to party.” She sat for a long moment before suddenly finding the energy to gather the pens and posters. She tossed the pens and posters into the bag and headed toward the stairs, the scroll tucked under her arm. Upon reaching the bottom, she recognized an adjunct she had met on the panel during Campus Equity Week.

He asked her if she needed help. He had come for midterm conferences, but none of his students had attended their meetings. Halloween is a big day in Chicago.

She said, “Yes, I need help carrying this stuff. I want to put the scroll up, but I need some way to attach it.”

He smiled and said, “I would love to help you with that.” He had been teaching for 20 years at her school, two classes a semester, but also at other universities in downtown Chicago. He had come to the forum on Wednesday and participated in the discussion.

“I want to help. Let’s do this. Let’s do this together!” he said happily.

They went to the bookstore to buy some packaging tape. Afterward, they walked over to the Office of Academic Affairs, and the coast was clear: there was absolutely nobody there. Of course, they had all gone home early on Halloween, or maybe they were attending a party, but even the administrative assistants weren’t there. They attached the scroll with the packaging tape to the wall by the elevator, and he took several photos of Heather, who didn’t bother to wear a mask or a hat. She left the posters she had made taped to the large windows that led up to their offices. She wished she could see their faces when they returned to work on Monday.

It’s hard to explain the significance of not being alone. Being a Gadfly is one thing, but having a fellow adjunct willing to march down the hallways alongside her and attach that scroll to the doors of their offices made her recognize how difficult it was to stand up to the administration. She felt empowered and connected to other activists who had encouraged her to stand up for adjunct rights on this day. And this time, she didn’t have a bag over her head. She walked, smiling and talking to her new friend, who helped her carry everything back to her office.

That night, one of her students, Jenna, emailed requesting an appointment during office hours the next day to review for the midterm. She invited her to come to her office an hour before class. She showed up even before she had a chance to open the door. She tried to help her with the concepts she’d covered in class, but instead, they ended up discussing foster children and how difficult it was for them to survive as they grew up in Chicago. Jenna admitted she was also a student of Manuel’s, and he had suggested that she talk to Heather about the recent legislation in the state legislature to extend the time the state provides relief for foster children until 21. She wondered if Heather would sign a petition and come to a meeting on campus to support foster children and reach out to them on campus. She agreed to help her with great enthusiasm.

Jenna went on to say that her mom died when she was a toddler and that she had been in the foster care system ever since, shuttled between different homes until she met her husband. She worked extremely hard in high school to earn good grades, even when she was kicked out of one family, sent to another, and forced to change schools. After school, she worked at a fast-food place, saving as much money as possible in the hopes of finding a way to live independently when she turned eighteen.

She told me that almost all her friends she’d stayed in contact with, who grew up in foster care, were either homeless, in jail, or dead now. However, she visited the ones in jail and called them when she could not see them. She brought food and clothing to those she could find on the street. She told me about her two young children and how hard she had worked to be a good mom to them in every way. To her, it was a sacred calling to have a family of her own. Her husband supported her and helped her pay tuition at college. She was enrolled in the social work program. Her dream was to help future foster children caught in the same system. She said the worst part was when they reached eighteen; the families just sent them away, and there weren’t any funds to help them pay for college or find a safe, affordable place to live.

Heather told her about her foster sister, Genevieve, that afternoon. She started crying despite herself. She explained how much she missed her and how guilty she felt. She told Jenna that she was one of the few people to whom she had revealed the whole story.

Jenna grabbed her hands with tears in her eyes, “Thank you for protecting her. Thank you for being there for her. You can only do so much. She knew her time was up, just the way we all do. It’s part of the package. You are only welcome for so long.”

That’s probably the closest she’d come to being absolved of the guilt she’d carried since Genevieve ran away. While it didn't ease her pain knowing that so many other children suffered as she did, it did matter that this young woman acknowledged her love for Genevieve in a way no one else ever had.

This is the final chapter of An Adjunct Story, but the story continues with a look backwards at the younger life of Heather Carmichael and why she became an adjunct activist. Next up? Part 2: Genevieve.