Then, suddenly, there was an anonymous call from an adjunct in California for all adjuncts to walk out of their classrooms: National Adjunct Walkout Day. It started with rumors on Twitter and quickly spread to Facebook groups across the country. By the time it occurred in February, adjuncts from Europe, Canada, and Australia were also planning to participate. The group “Precarious Faculty” created a map that grew larger throughout the winter, continuously updating all the colleges involved in the walkout scheduled for February 25, 2015.

The national media had deemed the story interesting enough to cover. Heather’s mother sent her clippings from the Boston Globe, detailing the organizing efforts in Boston and Cambridge. Adjuncts at Northeastern University were making significant progress as they unionized and worked closely with students to inform the press of their support for their efforts.

Heather’s mother had taught full-time at Lesley College, where the current focus was primarily on unionizing part-time faculty. She told Heather during a lengthy phone call that she believed the new slogan for the Adjunct Movement should be “Fare Forward!” Heather loved this slogan, which originated from the poem “The Dry Salvages” by T.S. Eliot, the third poem of his great work “The Four Quartets”:

“At the moment, which is neither action nor inaction

You can receive this: “on whatever sphere of being

The mind of a man is intent

At the time of death: - that is the one action.

(and the time of death is every moment)

Which shall fructify in the lives of others:

And do not think of the fruit of action.

Fare forward.

O voyagers, O seamen,

You who come to port, and you whose bodies

Will suffer the trial and the judgment of the sea,

Or whatever event, this is your real destination.’

So Krishna, as when he admonished Arjuna

On the field of battle.

Not farewell,

But fare forward, voyagers.”

The meaning behind those words became her call to move forward without looking back at the history that had brought higher education to this place. Her mom asked her to mail a Campus Equity T-shirt and button to Western Massachusetts. She was proud of her efforts to help fellow instructors in the struggle for adjunct justice.

Her mother had thrived in her career as a non-tenured professor. At 85, she recognized how much worse the situation was for adjunct faculty now compared to when she was teaching reading strategies to graduate students at Lesley College. She had a decent pension, and although her salary was not high, it provided full benefits that helped immensely after she retired. Those benefits continued after Heather’s father died and made it possible for her to live independently.

With the help of Manuel and the union, Heather began organizing the National Adjunct Walkout Day Teach-In (NAWD). The most important aspect for her was that the instructors serve as panelists. She encouraged other instructors to lead the discussion. One might think this wouldn’t be a big deal.

Heather was fifty-five years old and had been very involved in the Women’s Movement during her college years. She helped establish a Women’s Center on campus almost thirty-five years ago. She remembered how crucial it was to create a safe space for women that provided the resources to explore together what it meant to be a woman in their society.

They never invited men to speak at their workshops. They reached out to women on campus, women on the faculty, and women in the community while organizing feminist discussion groups, book groups, rape awareness workshops, lesbian support groups, poetry readings, and concerts.

One thing about tenured faculty, especially politically active liberal tenured faculty, is that they don’t like to give up control. Some of them were young enough that they hadn’t experienced the women’s liberation movement in the firsthand way Heather had. They couldn’t understand why she was so focused on letting the instructors have the only voices on the panel.

Nevertheless, she plowed ahead with Manuel’s help and with Sarah, whom she had upset so much by resigning from the Faculty Senate. Manuel was right; she was a very important person to have on their team. Sarah was an instructor, a full-time, exhausted instructor, but not a tenured professor. She was also an excellent writer. The three of them decided that one way to get students to attend the Teach-In was to ask faculty who supported their efforts to read a statement in class. They worked on it for weeks as a team, passing emails back and forth.

They came up with this statement:

Our faculty—tenured, tenure-track instructors, and adjuncts—are highly qualified and care deeply about our students’ learning and lives. They aim to create the most rewarding and engaging class experiences. But love doesn’t pay the bills.

I’m sharing this because February 25th is National Adjunct Walkout Day. Across the country, adjunct faculty and instructors—university professors who work on a temporary, semester, or year-to-year basis—are participating in teach-ins, class walkouts, rallies, and other forms of direct action and political education. While we are not organizing a walkout, there will be a teach-in from 12 to 2 PM and information tables in the Village Square from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

They started searching for speakers and ways to raise the student body's awareness of the lives of part-time professors and how this precarity affected the students’ education. Heather loved how easy it was to reserve a space for tabling and a television with computer access for continuous playback. She put together a playlist on YouTube, and many of her underground adjunct activist friends from Columbia College, SEIU Faculty Congress, and Loyola sent her links to significant organizing efforts. She was also able to reserve a conference room for the Teach-In itself.

Heather noticed that larger state schools, such as the University of Ohio, employed significantly more adjuncts than smaller private institutions. However, adjuncts were also abundant at community colleges and larger Catholic universities. CUNY (City University of New York) in New York City is the largest urban university system in the United States. Adjuncts at CUNY were organizing for a one-day strike, though striking was technically illegal because the union had previously agreed not to strike during their contract negotiations.

She became aware of this dynamic while touring colleges with Jonathan. Flippant remarks were made, such as, “We don’t have adjuncts here.” At that time, Heather felt annoyed because it seemed they were belittling her work. At one point, Jonathan told the student tour guide at Amherst College, “Be careful when you say that. My mom is a music instructor.” She laughed and hugged him. He also raised his eyebrows when the same tour guide showed them the post office and remarked that the staff there “taught” the students how to mail a letter. He whispered to her, “You need to go to Amherst to learn how to mail a letter?”

Every adjunct seemed to agree on the importance of making themselves visible. In many ways, Adjunct Walkout Day resembled Adjunct Coming Out Day. The ‘A is for Adjunct’ button that Anna had worn during Campus Equity Week was everywhere. The goal was to saturate the media with images of part-time faculty visibly asserting their existence. Tenured faculty were beginning to want to help, but most of them appeared to be more motivated to increase the number of tenured positions. As adjuncts took over much of the classroom instruction, the tenured professors felt overwhelmed by the demands placed on them by the university. It was exhausting to work so hard with so little support from the university community and its academic departments.

However, Heather believed that these tenured faculty did not genuinely want to assist the contingent faculty already in place. She had witnessed this pattern within her department. In all the department searches for tenure track positions she observed, not a single candidate emerged from the pool of instructors who were already working there. For her, it was a matter of equity. If the university hired these instructors for specific teaching responsibilities, they should be compensated with a living wage. In no other profession are such highly trained individuals treated so poorly.

A new issue had become apparent for instructors at her university. As the university reduced full-time instructors from 100% to 75%, and some even to 50%, they received emails requesting repayment of their wages from the fall semester. When their classes were canceled after the semester started, payroll hadn’t adjusted their paychecks. With spring enrollment even lower, they were asked to return a portion of their salaries. They then learned they would lose even more money due to the university's inability to manage payroll responsibly. This impacted their healthcare, as their premiums increased when they were changed to part-time status. The instructors were not only angry but also scared at this point.

She continued attending the union meetings, informing people they were organizing the event in February and inviting others to participate. Some days were harder than others as she tried to apply the inside-outside strategy that Joe Berry had articulated in “Reclaiming the Ivory Tower.” She even brought the book to school and kept it on her office shelf. If there was free time before a union meeting, she reread that section and tried to devise a winnable strategy to reach out to other instructors and tenured faculty for solidarity. Manuel insisted that she not alienate the other union members, as she had in the past.

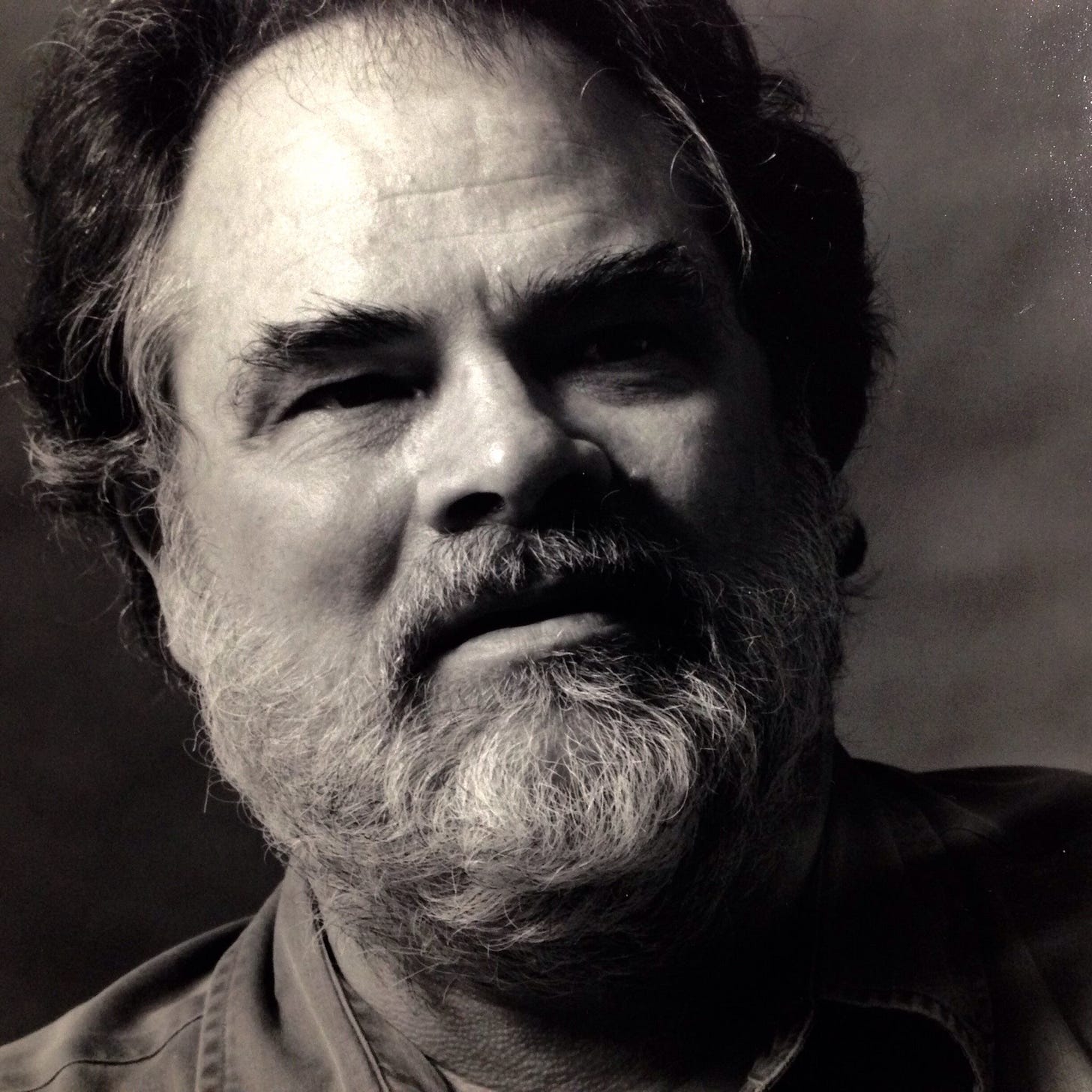

Then, one day, Heather received a phone call from Larry Duncan on her office phone. Larry was the videographer and film editor for Labor Beat, a local television show highlighting labor struggles in Chicago and across the country. He had launched his show on cable TV but later realized that YouTube was a more suitable platform. Larry was passionate about rank-and-file workers and discovered Heather through the network of labor stories circulating in Chicago. He was incredibly friendly and encouraging over the phone. They arranged a time to meet on campus, where he met her in the parking lot so she could provide him with a free parking pass. It felt almost too good to be true. He had found her! Sometimes, the inside-outside strategy wasn’t necessary when the outside found someone on the inside.

She walked him around the campus, wearing her ‘A is for Adjunct’ button. He asked if there were more buttons available for National Adjunct Walkout Day. She replied, “I’m sorry. No. I got this in Washington, D.C. last summer when I attended the Faculty Forward Congress. “

He smiled. “No need to worry. I have a button maker at home. If you lend that to me, I’ll make 500 buttons for the event. It might not be as bright red as yours, but it will get the job done.”

Heather’s eyes filled with tears; it contrasted sharply with the sensation she felt when the union professor chastised her for expecting to present her slides at the Inequality Initiative Roundtable. She said with emotion, “You would do that for us?”

“This is a labor of love. I have a passion for the rank-and-file worker, and adjuncts are in great company when it comes to being at the bottom of the workplace paradigm.”

“Thank you so much!” She unhooked the pin, closed it carefully, and handed it to him.

He answered, “I’ll take good care of it. I promise!”

Eliot, T. S., et al. Four Quartets. Rampant Lions Press, 1996.

Larry Duncan, 1945-2018. Champion of Adjunct Professors.